I wind up in occasional discussions on Twitter that are slightly awkward. My Twitter presence grew around my efforts to market my book, and, since that book features black and Hispanic characters, my environment on Twitter is dominated by black and Hispanic readers and writers. Discussions of white privilege and similar topics fly back and forth. It’s easy to participate when the discussion and my own opinion line up: when it comes to the topic of racial discrimination, I’m firmly against it, so I don’t have any problem being in general agreement.

I wind up in occasional discussions on Twitter that are slightly awkward. My Twitter presence grew around my efforts to market my book, and, since that book features black and Hispanic characters, my environment on Twitter is dominated by black and Hispanic readers and writers. Discussions of white privilege and similar topics fly back and forth. It’s easy to participate when the discussion and my own opinion line up: when it comes to the topic of racial discrimination, I’m firmly against it, so I don’t have any problem being in general agreement.

Other times, my fit isn’t quite so comfortable: maybe I think that people are overstating something, forgetting a historical perspective, or falling a bit too far into the “white men are the root of all evil” camp. Sometimes, I venture an opinion, sometimes I stay quiet: it depends on how firm I feel the ground is under my feet and how readily I think my opinion can be summed up in 140 characters without being open to misinterpretation.

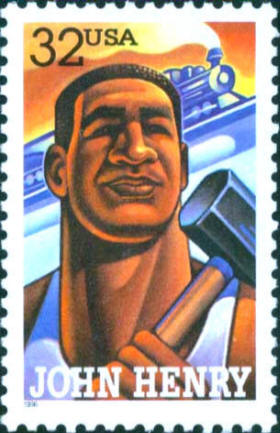

Today, the topic of John Henry came up. One of the accounts I follow, @Skyliting, lamented that one of her younger co-workers had never heard the song John Henry. We got into one of those short, choppy discussions that Twitter breeds. Skyliting was of the opinion that it was being edited out of school curricula because it made white children feel bad about things their ancestors had done, while I opined that I had never thought of the story of John Henry as a story of white mistreatment of blacks, but more of a story of corporate greed vs. the working man, with John Henry serving as a symbol of all labourers, white and black alike.

Just in case there are those of you that also don’t know the story of John Henry, it’s a simple tale, even though there are probably a thousand slightly different versions of the song, probably based on a combination of two or three different historical figures. John Henry was either born a slave or the child of a former slave. When he was quite young (usually as a “little baby, sitting on his pappy’s knee”) he had a vision that he would die because of a hammer. He became a steel-driver on the railroad, marrying Polly Ann, an unusual woman in that she could also drive steel and would fill in on the rare days that John got sick. “Steel driving”, by the way, is the arduous task of pounding holes into rock with a steel spike in order to place a dynamite charge.

To say that John Henry was a steel-driver is an understatement: he was a steel-driver of legendary skill and power, wielding a pair of nine-pound hammers that allowed him to do the work of any two other men. Different versions of the song expand on his exploits in different ways, but the final chapter is always the same: when the railroad decided to replace its steel drivers with a machine, John Henry wagered that he could beat the machine, that he’d either save the men’s jobs or he’d die with that hammer in his hand. As it turned out, he did beat the machine in a day-long race, pounding his way through fifteen feet of rock compared to the machine’s nine, whereupon he fell over and died.

Back to the discussion between me and Skyliting: I’ve been wracking my brain. Have I missed something in this story? Perhaps I have. One thing I’ve learned is that it’s always possible that I’ve missed something, and it’s a very, very, dangerous thing to presume that my whiteness hasn’t blinded me to something in a story about a black man.

Still, I go back to how I was taught as an extremely white little boy in an extremely white little Midwestern town: John Henry was a man. He was a man that stood up, a man that fought, a man that defended his friends, a man that defended his family, a man that defended a way of life, a man that fought an unwinnable fight because he did not know how to give up. That he lost by winning didn’t tarnish his character in the slightest. I, that little white boy in Nebraska, was supposed to view John Henry as a role model of strength and courage. Gerardo, the only black student in my class, was also supposed to view John Henry as a role model.

I can’t remember anyone ever mentioning anything to make me think that John Henry was some kind of other or outsider because he was black, or that I should view him as an exception to some general rule about not treating black people as role models.

I was taught about John Henry in the same course that I was taught about Paul Bunyan, Davy Crockett, Pecos Bill, and all the other folk heroes. John Henry stood proud and tall among those men, an example of the foundation upon which my country had been built.

It’s possible that Skyliting is 100% right, that John Henry is being edited out of school curricula out of some form of white shame. I hope she’s not. When we talk about diversity in literature, an important part of that diversity is to teach our children not to think about those characters always as “like me” or “not like me”, but to teach children to empathize with with everyone. We include black characters in stories not only to allow black children to have heroes, but to allow white children to recognize that blacks can be heroes too.