The Skatalites pose for a publicity shot

Regular readers might remember my existential crisis last year, when Jamie Broadnax expressed hesitation over my Black History Month suggestions, replete as they were with blood, vengeance, uprisings, and just plain general misery. My softer side won out, and I wound up writing a little piece reminding people that the banjo was an African invention. This Black History month, it’s another study of black musical history as I look at a musical style that Jamaica gave to the world: ska.

This year, I found myself at Ska Wars 2016, the largest ska festival in the United States. My daughter’s new home is within walking distance of the venue, so it was easy to persuade my wife to drive the 400 miles to Los Angeles with me even though she had never heard of Los De Abajo, Nana Pancha, Out of Control Army, La Resistencia, or any of the other headliners. She wasn’t going to be listening to them anyway, so what did it matter to her? The myriad of smaller local bands playing the festival were unknown to me as well, but what did I care? It was an adventure, something this old man needs a bit more of.

This year, I found myself at Ska Wars 2016, the largest ska festival in the United States. My daughter’s new home is within walking distance of the venue, so it was easy to persuade my wife to drive the 400 miles to Los Angeles with me even though she had never heard of Los De Abajo, Nana Pancha, Out of Control Army, La Resistencia, or any of the other headliners. She wasn’t going to be listening to them anyway, so what did it matter to her? The myriad of smaller local bands playing the festival were unknown to me as well, but what did I care? It was an adventure, something this old man needs a bit more of.

So, there I was on a solo day out, one of a small handful of whites, joined by an even smaller group of blacks, in this enormous sea of Hispanic rude boys and Hispanic skinheads and Hispanic punks, happily skanking along in peace and harmony to The Steady 45s doing a ska rendition of The Shirelles’ Mama Said, when I realized that we probably have an entire generation of people that don’t think of ska as a genre of black music. Strangely enough, it has become a genre of Latin music, performed in combination with cumbia, merengue, salsa, and rhumba.

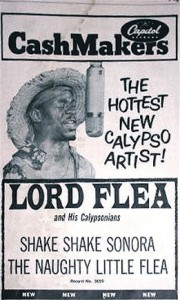

When you go back in history, ska was an exclusively black musical genre, an offshoot of mento. Mento, a Caribbean music style noted for its syncopated rhythm (essentially a series of off-beat triplets), was usually played by small groups: typically a vocalist, a tongue-drum, a banjo, and a guitar. It’s a cousin to calypso music, and, despite being rhythmically distinct, the two forms were generally marketed as calypso in the US: most Harry Belafonte songs were actually mento, not calypso. As Lord Flea (Norman Thomas) explained,

“In Jamaica, we call our music ‘mento’ until very recently. Today, ‘calypso’ is beginning to be used for all kinds of West Indian music. This is because it’s become so commercialized there. Some people like to think of West Indians as carefree natives who work and sing and play and laugh their lives away. But this isn’t so. Most of the people there are hard working folks, and many of them are smart business men. If the tourists want ‘calypso’, that’s what we sell them.“

“In Jamaica, we call our music ‘mento’ until very recently. Today, ‘calypso’ is beginning to be used for all kinds of West Indian music. This is because it’s become so commercialized there. Some people like to think of West Indians as carefree natives who work and sing and play and laugh their lives away. But this isn’t so. Most of the people there are hard working folks, and many of them are smart business men. If the tourists want ‘calypso’, that’s what we sell them.“

Today, mento is viewed primarily as a form of Jamaican roots music. Only The Jolly Boys have made any headway in terms of presenting mento to modern audiences, and their cover of Perfect Day is a textbook example of the rhythm. Click that link and get a feel for the syncopation: that beat is present in some form in the entire bluebeat music family. Get used to that word: Bluebeat Records was a major player in its day, and “bluebeat” is sometimes used to refer to the mento/ska/reggae/rocksteady/dancehall/dub music family.

In the late 1950’s, Jamaican musicians began to incorporate American R&B sounds into mento, and the hybrid form stabilized on using the same syncopated structure with an even stronger off-beat chord known as the skank (bonus info for music theorists: the skank in ska is nearly always a major chord, while in reggae it’s generally a minor chord). Typical instrumentation was a guitar, a bass (sometimes a bass guitar, but just as often a concert bass), drum, saxophone, trumpet, and trombone: still the core ska band today, although some bands have much larger horn sections. Many of the musicians of this era are familiar today as reggae and rocksteady musicians: Bob Marley probably being the most famous to American audiences, with names such as Toots Hibbert (reputed to have actually invented reggae) and Desmond Dekker still having some familiarity.

To a true ska afficianado, however, the band that defined the style was The Skatalites. The Skatalites used a horn-heavy styling that persists in distinguishing ska from other forms of bluebeat music, and, as Studio One’s house musicians, they influenced the sound of nearly every ska performer in the early days. By 1962, when independence was finally achieved, ska was so pervasive in Jamaican society that even the Jamaican Independence Song is a ska number.

While today we associate ska with a frenetic tempo, that’s not present in the earliest recordings. It’s always been a dance rhythm, but classics such as Guns of Navarone and Eastern Western Time are laid back, relatively mellow musical pieces.

Music doesn’t stand still anywhere, and bluebeat transformed into rocksteady and reggae. By 1969, nearly every ska performer had moved with the times, with ska not quite falling by the wayside, but certainly fading in popularity compared to its cousins. It wasn’t until the Two Tone movement hit Britain in the late 1970s that ska became popular again, performed by such groups as The Specials, The Selecter, Bad Manners, and Madness. The Two Tone sound added a punk flavor to the ska (music theorists will note the frequent substitution of power chords on the skank over the original major chords) and an faster, more driving beat. British ska bands were strongly associated with the skinhead look. Ironically, the skinheads themselves eventually became associated with racist movements, so a formerly black musical genre became loosely tied to anti-black racism.

Music doesn’t stand still anywhere, and bluebeat transformed into rocksteady and reggae. By 1969, nearly every ska performer had moved with the times, with ska not quite falling by the wayside, but certainly fading in popularity compared to its cousins. It wasn’t until the Two Tone movement hit Britain in the late 1970s that ska became popular again, performed by such groups as The Specials, The Selecter, Bad Manners, and Madness. The Two Tone sound added a punk flavor to the ska (music theorists will note the frequent substitution of power chords on the skank over the original major chords) and an faster, more driving beat. British ska bands were strongly associated with the skinhead look. Ironically, the skinheads themselves eventually became associated with racist movements, so a formerly black musical genre became loosely tied to anti-black racism.

By the late ’80’s, Two Tone ska was largely replaced by the third wave of ska, a California-based style that continued with slightly reduced punk influences and a renewed emphasis on horns. That’s only a generality, though: there isn’t a general agreement as to any particular musical characteristic that distinguishes the third wave from Two Tone. It only takes a few minutes of listening to No Doubt and comparing them to The Mighty Mighty Bosstones to recognize that “third-wave ska” is a broad umbrella.

Now, we are experiencing Latin ska resurgence. It’s not particularly surprising that ska has caught on in Latin America: take a quick listen to a band like Chico Trujillo, which describes itself as cumbia band. The raw ingredients of ska are all there, just a slightly different rhythm. The Mexican mariachi band has a similar composition, a mix of guitars, vocals and horns. Salsa and mambo are rooted in the horn-heavy big-band style: witness Perez Prado and Tito Puente. It’s no wonder that Latin Americans growing up with those traditions adopted ska.

And adopt it they did: today, most ska is performed in Spanish. The powerhouses of ska aren’t bands that are familiar to most Americans, having names like Los Fabulosos Cadillacs, Nana Pancha, Inspector, and Los De Abajo.

But, since this is a black history month article, after all, let’s talk about who a serious student of ska would look at in those early years. We’ve talked about The Skatalites (and, as you will see, we will continue to talk about The Skatalites). Who else?

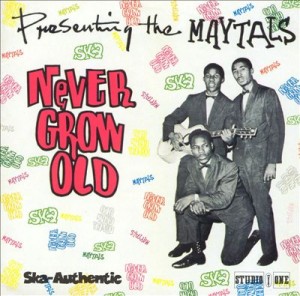

Toots Hibbert (who is said to have recorded the first reggae song) led Toots & The Maytals, backed by Henry Gordon and Nathaniel Mathias. Toots & The Maytals had a long career, spanning from 1961 to 2013, only breaking up when Toots was hit by a vodka bottle thrown by an unruly fan during a concert (forgive me if I view this as a negative side effect of the growing impact of punk music on ska). Today, they are probably best known for doing the original recording of “Monkey Man”, a song which has since been covered by every ska band in existence (and even Kylie Minogue and the Wiggles, but I refuse to link to that one … find it yourself if you must). During their early years, Toots & The Maytals were under contract to Studio One, performing three-part harmony on top of backing music laid by The Skatalites.

Toots Hibbert (who is said to have recorded the first reggae song) led Toots & The Maytals, backed by Henry Gordon and Nathaniel Mathias. Toots & The Maytals had a long career, spanning from 1961 to 2013, only breaking up when Toots was hit by a vodka bottle thrown by an unruly fan during a concert (forgive me if I view this as a negative side effect of the growing impact of punk music on ska). Today, they are probably best known for doing the original recording of “Monkey Man”, a song which has since been covered by every ska band in existence (and even Kylie Minogue and the Wiggles, but I refuse to link to that one … find it yourself if you must). During their early years, Toots & The Maytals were under contract to Studio One, performing three-part harmony on top of backing music laid by The Skatalites.

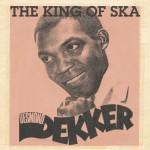

In more hybridization, Henry Gordon and Nathaniel Mathias decided that being “& The Maytals” wasn’t prestigious enough and tried their hand at being “& The Cherry Pies”, backing Desmond Dekker on his first big hit, King of Ska (where, of course, The Skatalites provided the backing music). They quickly returned to their career as the Maytals, with Desmond Dekker moving on to Desmond Dekker & The Aces. Dekker was a foundational ska performer but became better known for his rocksteady: The Israelites and Fu Manchu being his signature pieces.

In more hybridization, Henry Gordon and Nathaniel Mathias decided that being “& The Maytals” wasn’t prestigious enough and tried their hand at being “& The Cherry Pies”, backing Desmond Dekker on his first big hit, King of Ska (where, of course, The Skatalites provided the backing music). They quickly returned to their career as the Maytals, with Desmond Dekker moving on to Desmond Dekker & The Aces. Dekker was a foundational ska performer but became better known for his rocksteady: The Israelites and Fu Manchu being his signature pieces.

Unsurprisingly, Bob Marley & The Wailers got their start in ska, releasing many songs for Studio One. They are famous enough that I don’t think the average reader is going to need much help finding out about them.

The Ethiopians, while frequently called a ska band, actually performed far more rocksteady, and can be reasonably viewed as a driving force in the transition away from ska towards rocksteady.

The Ethiopians, while frequently called a ska band, actually performed far more rocksteady, and can be reasonably viewed as a driving force in the transition away from ska towards rocksteady.

Prince Buster , more formally known as Cecil Bustamente Campbell, is an exception to the general Rastafarian dominance of the Jamaican music scene, joining the Nation of Islam in 1964. His private label, appropriately named “Islam”, released such items as a reggae-backed version of Louis Farrakhan’s “A White Man’s Heaven is a Black Man’s Hell“.

, more formally known as Cecil Bustamente Campbell, is an exception to the general Rastafarian dominance of the Jamaican music scene, joining the Nation of Islam in 1964. His private label, appropriately named “Islam”, released such items as a reggae-backed version of Louis Farrakhan’s “A White Man’s Heaven is a Black Man’s Hell“.

I can’t call this a definitive history of ska, but this should be enough to give you a flavor. Go back and click any of those links you skipped over: I’ve combed YouTube and built playlists that should give you a taste of each of these artists.