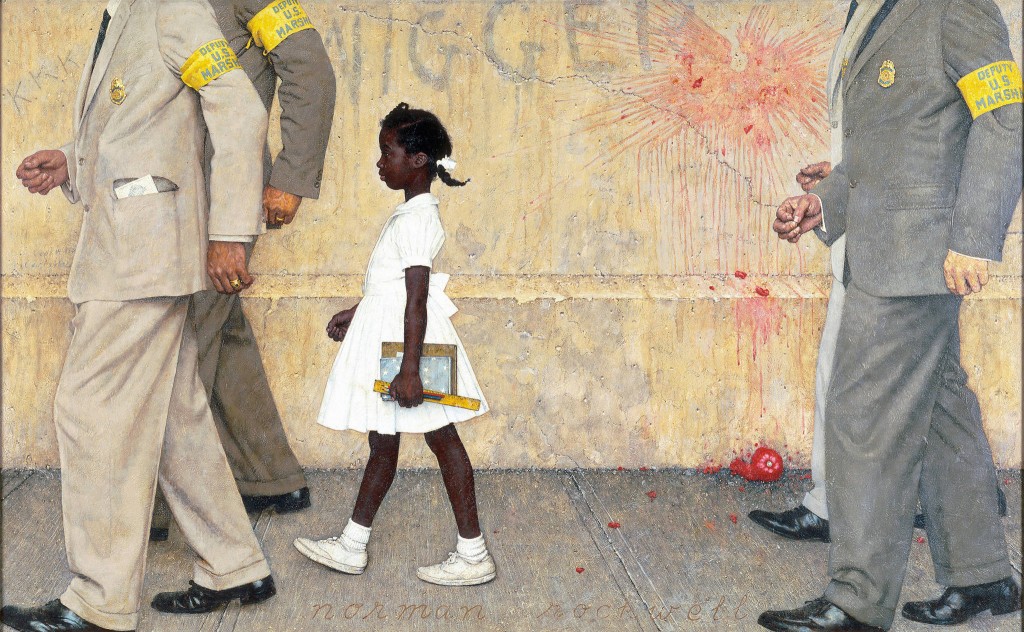

President Barack Obama, Ruby Bridges, and representatives of the Norman Rockwell Museum view Rockwell’s “The Problem We All Live With”, hanging in a West Wing hallway near the Oval Office, July 15, 2011. (Official White House Photo by Pete Souza)

If, like me, you grew up in the 1960s, then pictures by Norman Rockwell were inescapable: something like Thomas Kinkade, but Rockwell actually had talent. A peculiarly constrained talent, though: generally images of cute white people doing cute white people things, suitable for the cover illustration of The Saturday Evening Post. I had never thought of that as really being unusual (having grown up as a cute white person myself), which means that I was surprised to find out in my later years that this restriction chafed on Rockwell, and he eventually left a lucrative contract with The Saturday Evening Post because of a contract restriction that only permitted him to display blacks in positions of servitude.

His debut with Look was the most famous of his “not about cute white people” paintings: one of Ruby Bridges, the first black child to attend a white school in New Orleans.

The Problem We All Live With, centerfold of the January 14, 1964 issue of Look.

The Problem We All Live With now hangs in the West Wing of the White House, on loan from the Norman Rockwell museum to Barack Obama. The imagery here is obvious: the clean and pure little black girl, ironically dressed all in white, surrounded by the filth and debris left by the whites around her. It doesn’t take much of an imagination to see the resemblance between the splats of the tomato on the wall and the feathered wings of the Nazi eagle.

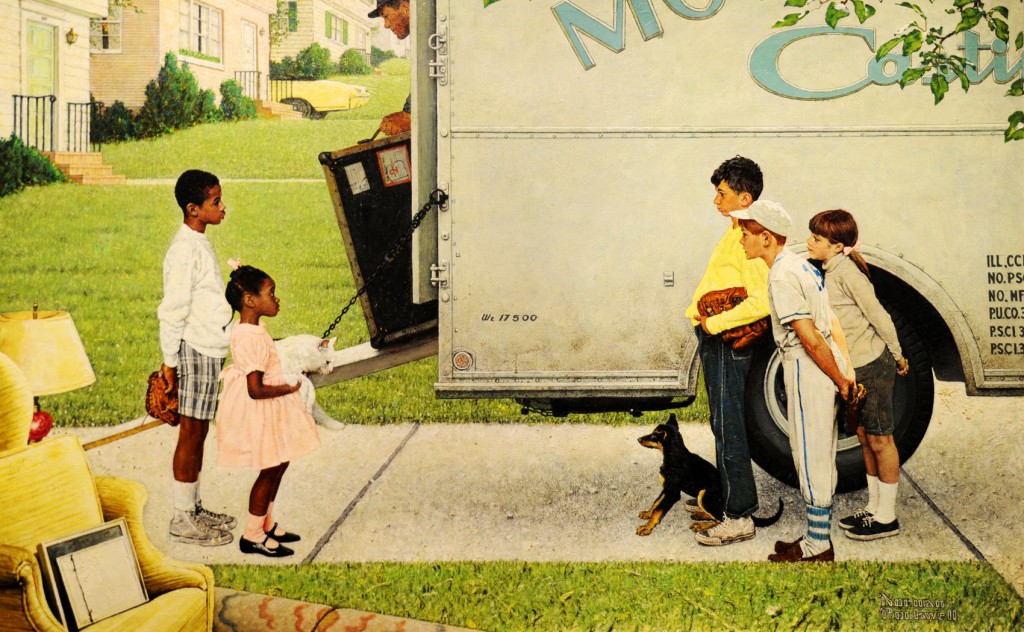

New Kids in the Neighborhood, 1967

In 1967, Look also published New Kids in the Neighborhood, a picture that strikes us as relatively uncontroversial today, but controversial in its day for the suggestion that once the surprise is over (look at the dog), the boys’ common love for baseball will win the day.

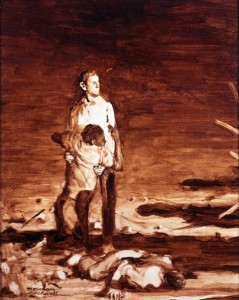

Oil sketch for Southern Justice

To my eyes, his most powerful piece was 1965’s Southern Justice (Murder in Mississippi), an illustration of the murder of James Chaney, a black, and two white Jewish youth from New York, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, who were brutally murdered by the KKK in Mississippi in 1964. Look magazine never did publish the completed work. Instead, they published an oil sketch which they claimed was more emotionally powerful than the finished work. I can’t say they are wrong: there’s a rawness to the quick version of the piece that works, and may well convey a stronger emotional punch than the finished version below.

Unpublished complete painting of Southern Justice (Murder in Mississippi)